Breeding Back

Breeding back is described as a natural or human attempt to re-assemble the genes of an extinct species. This practice is highly controversial and there are many geneticists who question whether it can even be thoroughly accomplished in any extinct animal breed. Others want to know what consequences there will be by adding these different species of wild animals back into an untamed environment. Even with these concerns many different programs have been created to breed back feral species of extinct animals and their endeavors continue with enthusiasm. To be sure, there are several advantages to breeding back. Namely, breeding back can produce a whole population of species rather than one individual, such as in the case of cloning.

Aurochs

Photo Credit: Mikael Parkvall

The Aurochs was a large species of cattle dating as far back as 2 million years ago and living until almost 400 years ago. Evidence of these giant cattle remain in prehistoric cave paintings as a historical testament to their once prolific existence throughout Europe and Asia. This giant herbivore freely roamed Europe and Asia and some say it was a fierce adversary when hunted.

The Aurochs was domesticated around 8,000 years ago when it was used for meat and to pull heavy loads. They, unfortunately, became extinct in 1627 when the last surviving Aurochs, a female at Jaktorow Forest Reserve in Poland, died at the hands of a poacher.

It has recently been discovered, however, that some modern cattle possess several matching genes with the Aurochs. Both the Spanish Fighting bulls as well as the Highland and English Park Cattle have been found to retain some of these genes. Stichting Taurus, a Dutch preservationist group, is now leading the project to breed these animals and produce a separate breed of cattle, called Heck Cattle, that only possesses the original Aurochs genes. Their aim is to eventually release these animals back into the wild Dutch countryside to once again flourish in a reestablished ecosystem.

Some scientists disagree that all of the original Aurochs genes will be able to be repositioned and thus the project to breed back the Aurochs will never be completed. Johan van Arendonk, a professor of animal breeding and genetics at Wageningen University in the Netherlands, notes that a population needs to be adaptive in order to survive. This means that over 100 cattle will need to be maintained before they can be released into the wild. Therefore, this project is expected to take many more years to complete.

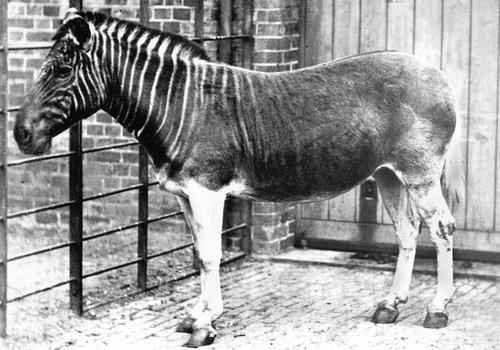

Quagga

The Quagga was a subspecies of zebra. As far as can be proven, the coloration of the Quagga is the only difference between a zebra of the north and the plains zebras in the south. The Quagga was hunted to extinction as they were seen by settlers to be competition for the limited grazing land of the African plains. The last surviving Quagga died in 1883 in an African zoo.

But the Quagga served a purpose in the ecosystem of the African plains and a group in South Africa began the Quagga Project in 1987 to breed back this unique subspecies of zebra. Again, some scientists disagree that this project will bring back the original Quagga, even though the project coordinators are using information gathered from Quagga material still in existence. The argument is that the Quagga may have developed unknown adaptations specific to environmental needs of which the project coordinators are not yet aware. The Quagga Project continues their quest without funding from any government entity or large endorsements. They breed and house their bred back Quagga population solely from individual donations and local interest volunteers.

Heck Horse

The Tarpan is a prehistoric horse that ranged from southern France and Spain to central Russia. Prehistoric cave paintings have been found depicting the Tarpan in numerous events. The Tarpan was domesticated by Scythian nomads 3,000 years ago.

The original wild Tarpan died out in the 1800s due to human population growth. At that time, the Tarpan was seen as a competitor for farmland and many treated the Tarpan as a nuisance that stole their mares and ate their crops. The last surviving Tarpan died in a Ukrainian Game Preserve in 1876.

The Heck Horse was a project started in 1933 by two German zoologists named Heinz and Lutz Heck. They believed that the Tarpan could be bred back because, as they speculated, certain domesticated European horses must have descended from the Tarpan still retaining DNA from this original European wild horse. Today, the Heck Horse is bred both in the wild and as domesticated riding horses. They are currently maintained by the North American Tarpan Association.

Mammoth

The Mammoth was a prehistoric Pachyderm living during the Pleistocene Epoch. Many preserved specimens have been found intact in the permafrost of Eastern Siberia. The species is said to have become extinct around the end of our Earth's last ice age about 12,000 years ago, although myths still remain from people claiming to have spotted a large woolly creature in northern Alaska.

Because researchers have been able to extract DNA samples from the preserved hair follicles of this massive extinct mammal, they have now been able to map 50% of the mammoth's genes. Plans are now underway to use cloning technology to insert genetic mammoth material into an elephant's egg and implant the mammoth embryo into an elephant's womb. This experiment has already been successful using mice and if they are successful, the Tokyo based project could produce a live mammoth baby in as few as 3 to 5 years.

Breeding Back the Dire Wolf

Stanley, an American Dirus dog

Unfortunately, no species of wolf living today is descended from the Dire Wolf and no one has found hair follicles or other living Dire Wolf tissue as is the case with the mammoth. Therefore, it is impossible to breed back the Dire Wolf using direct DNA. It is simply not available. Also, non-living bone material from Dire Wolf skeletons does not currently provide scientists with the ability to recreate the Dire Wolf as it was during the Pleistocene Epoch. If this were possible, Jurassic Park would not only be a distant fantasy portrayed in a large budget film but a ferocious reality.

Furthermore, the animals that have been bred back thus far have been herbivores lost in the last few centuries. Documentation of their existence, beyond that of educated scientific speculation, has been extensive. Pelts, pictures, skeletons, cave drawings, notes, articles, journals, etc. have all been provided for these relatively new extinct creatures. This creates a descriptive advantage for those wanting to breed back to a certain look and type that is just not present when thinking about breeding back the Dire Wolf. The only option to recreate the known features of the Dire Wolf, the bone and body structure, is to use existing animals from populations of species directly descended from the Gray Wolf.

Lobo, a DireWolf Dog

The aim of each of the above bred back animals is to eventually release them back into the wild. It is unlikely that any of these gentle species will cause undo harm to our current human population's needs, but may in fact, enhance the ecosystems where they had once thrived. Recreating a massive wild predator that tends to devour larger prey could potentially undermine the already threatened Timber wolf population as well as enrage farmers and many other local inhabitants.

For these reasons, the Dire Wolf Project, does not aim to breed back the Dire Wolf genealogically and morphologically. This is an obvious impossibility and truthfully undesired. The only recourse is to breed back the bone and body structure by exactly matching the Dire Wolf skeletons through selective breeding. The outward appearance of a bred back Dire Wolf can only be an educated guess, just as scientists pose theories of coat type and temperament based on skeletal remains. In addition, the Dire Wolf Project does not wish to create a ferocious predator and release such an animal into the wild. The other option, then, is to create a domesticated animal that can thrive peacefully in our current lifestyle. This limits such a program to using domesticated dog breeds that, when combined through selective breeding, have the correct genetic make-up to match the physical characteristics we know existed in the Dire Wolf.

Dingo, a DireWolf Dog

The Dire Wolf Project has done extensive research into the Dire Wolf's speculated health, temperament and appearance. With exact measurements, we can simulate a gentle domesticated dog breed that resembles the Dire Wolf in bone and body structure as well as the two coat color theory types that scientists have suggested. Selective breeding, when used for certain Dire Wolf characteristics, will slowly change the temperament and appearance to closely recreate a domesticated prehistoric predator. Exactly what will be staring back? The Dire Wolf Project aims to find out!

REFERENCES

* Breeding Ancient Cattle Back From Extinction. Faris, Stephan. Retrieved: 2011-05-29.

* Cows came from Aurochs 8500 years ago. Holladay, April. Retrieved: 2011-06-09.

* The Quagga Project. The Quagga Project South Africa. Retrieved: 2011-06-13.

* Tarpan Breed of Livestock. Oklahoma State University. Retrieved: 2011-06-13.

* Mammoth could be resurrected in five years. Cosmos Magazine. Retrieved: 2011-06-27.